When they were created in the early part of the sixteenth century, the boxwood prayer beads were unlike anything that had come before. They were built in two parts—exterior shells and inset reliefs—and this arrangement gave their maker(s) unfettered access to each element to sculpt complex, geometric patterns or actualize narrative scenes in the tiniest of fields.

The interior reliefs of the prayer beads are held in place with diminutive pegs that pass from the front, perimeter edge of the relief into the exterior shell. The pegs were always left projecting from the relief: sometimes they are hidden in the composition and may be difficult to discern. At other times, they are conspicuously implanted at quadrants of the circumference of the interior. Such a minimal approach successfully secured the relief and accommodated the variable expansion and contraction of the shell and relief. While it is impossible to know why the sculptor left the pegs visible, they may have been left accessible so that a goldsmith or jeweler would be able to remove the interior relief to add metal mounts to the exterior shell. It is also possible that the pegs were left conspicuous to draw attention to the prayer bead’s construction, underlining its virtuosity.

The prayer beads’ interiors were fabricated in a number of different ways. The least complex are simply boxwood discs carved in low relief with their backs rounded off. There are some examples of interiors, similarly carved from a single disc of boxwood, which are very deeply carved and contain figures sculpted in the round. A prayer bead in the Thomson Collection that illustrates the Queen of Sheba’s visit to King Solomon (AGO 29458) is an example of this. The only added element is a lamp on the side of the baldachin.

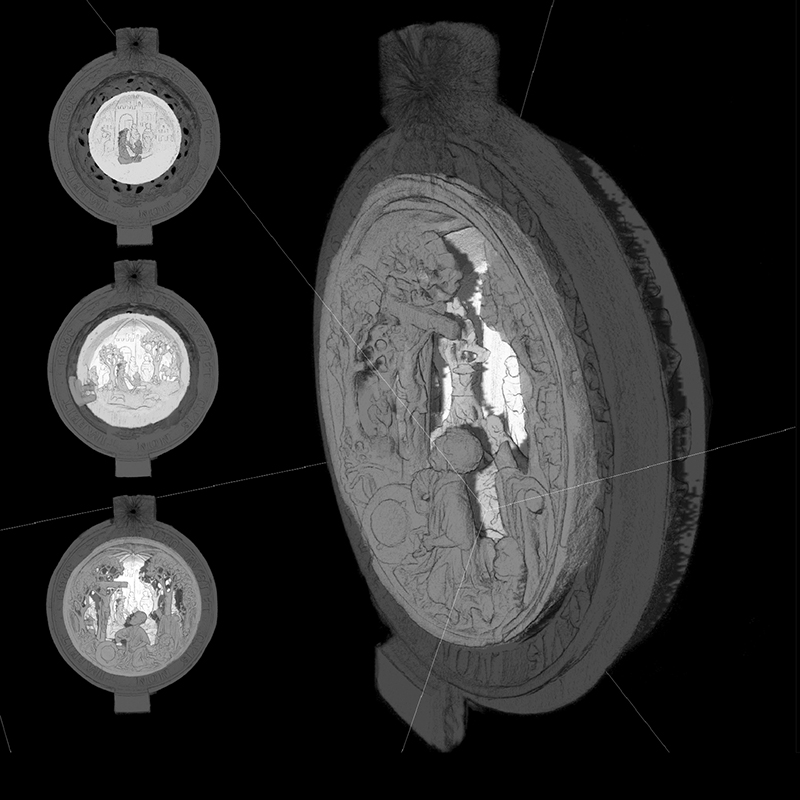

Comparison of a number of the more complex, multi-component prayer bead interiors reveals that several different approaches were executed in combining carved layers. Perhaps the most straightforward is exemplified in an AGO relief depicting St. Hubert (AGO 29359). Micro CT scans reveal that a solid disc was used in the background to depict a hunting party with rider on horse, huntsman with horn, and dogs in low relief. Overlying this is another disc into which the scene of St. Hubert’s revelation was carved. Unlike the scene behind it, the carver here has worked from both sides of the disc, opening up the negative space surrounding the trees, deer, and saint and exposing the hunting scene in the background. Inserted through the back panel, pins were used to join the discs together.

Another prayer bead in the Thomson Collection uses three layers to depict Jerome praying to the cross (AGO 29360); its deepest layer is solid and its front face is carved in relief. The two layers stacked on top of this are sculpted from both sides and pierced to reveal the underlying reliefs. The deepest disc is glued into a beveled mortise in the middle disc to which it is also secured with pins cut flush to the surface. The foremost disc is butt-joined and glued to the middle disc. This arrangement was designed to reduce the surface area around the perimeter needed for a more elaborate mechanical join, providing more space for the composition overall.

A set of extremely intricate prayer bead interiors is also constructed of a succession of stacked, pierced discs: these, however, become increasingly smaller from front to back and are offset. This design accommodates the depiction of a scene with a flattened foreground and a heightened vanishing point. The overall shape of these reliefs can be described as an oblique cone with its apex higher than its center.

These interiors are often further ornamented with added elements. The elaborate costumes and headdresses that were in fashion at the time were adopted for many of the figures populating the reliefs. To achieve the appropriate verve, discrete flourishes such as soldiers’ shields, shepherds’ staffs, buttons down the back of a jacket, or the finial on top of a soldier’s spiral helmet were discretely carved and set into drilled holes. In addition, common and virtuosic elements such as candles attached to a column or wall and rings that move freely for tying horses found on stone piers, were all set into or through similar mortises.

Illustrative of this construction method is an interior relief of the finest quality, comprised of four offset discs, in a prayer bead depicting the Crucifixion (MMA 17.190.473b). The discs slot into one another with an intricate system of beveled mortise and tenon joins and are secured with pins and pegs visible only on the exterior of the relief. This type of multi-disc construction also eliminated the need to provide an opening at the apex of the composition to allow sufficient access into an interior constructed, for example, from one or two discs.

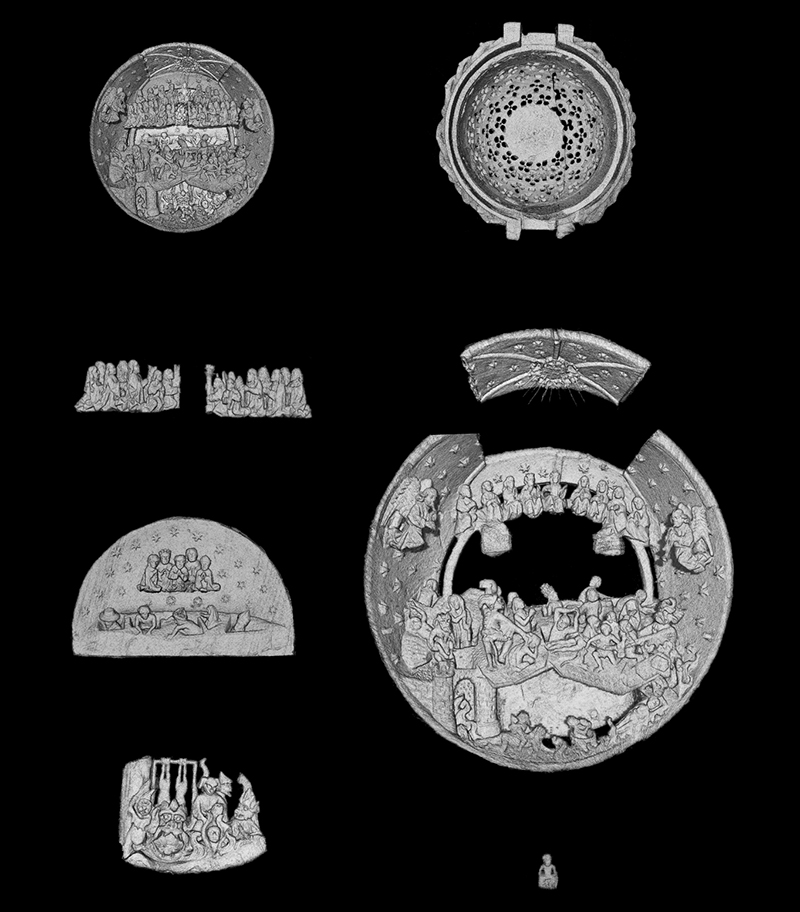

An exceptional interior carving, the Last Judgement (AGO 29365), shown on the following pages, takes advantage of just such an opening at the apex of the main disc. In addition to this aperture, the disc has an additional, sizeable opening in its back and a large slot in the bottom into which an additional sculpted element was introduced. The use of these apertures allowed the carver to fashion figures in the round throughout the composition. Numerous tiny additional elements supply further detail to this remarkable work: the most astonishing is a minuscule figure who has been inserted into the mouth of hell and whose anguished countenance is barely visible.

This Essay excerpted from Small Wonders: Gothic Boxwood Miniatures