When first discovering the intricate carvings in prayer beads and altarpieces, viewers most often respond with a sense of wonder. This effect fulfills, no doubt, part of the artist’s intention, as well as the desire of the original owner. Fascination is followed by a desire to understand how and by whom these extraordinary and delightful objects were made. Current technologies have allowed researchers to finally resolve the former, while the latter remains a mystery. [15]

In stark contrast to the boxwood miniatures, much is known about large-scale wooden altarpieces, or retables, produced in the Netherlands beginning in the middle of the fifteenth century and extending to the middle of the sixteenth century. [16] The size and complexity of the altarpieces required the collaboration of multiple artisans, who were usually organized into specialized guilds. These included sculptors, carvers, turners, joiners, painters, and carpenters. Segregation of their roles was most often controlled by somewhat idiosyncratic regulations that varied from town to town. Rules were enforced by guilds and their workers’ contributions were often indicated with stamps or other visual markers on the altarpieces. No such marks have been identified on the more diminutive boxwood objects by magnification, micro-CT scanning, or selective deconstruction. [17]

Of all the miniature boxwood carvings, only one has a somewhat ambiguous inscription, found on a prayer bead depicting the Carrying of the Cross, that could serve to identify a possible maker. [18] Carved into a band around the interior edge of the shell securing the relief is the inscription “Adam Theodrici me fecit.” The Latin expression “me fecit” translates to “made me,” and would seem to unequivocally designate Adam Theordici as the sculptor of this prayer bead, or possibly its surrounding shell. [19] However, this attribution is questionable as often sculptors were not identified on their works; instead, their patron, or the commissioner of the work, would be named. Correspondingly, carved coats of arms link some of the works to specific patrons, ranging from members of the monarchy to elevated church officials, and blank escutcheons intended to be either carved or painted with the identifying marks of owners are found on many objects.

Successive efforts by researchers to identify a specific artist or workshop associated with the boxwood objects in contemporaneous records or literature have been unsuccessful. Without this information, we have turned to the objects themselves and to the practices of their contemporaries to build a possible profile of the responsible artist(s). Artists creating both the large-scale altarpieces and the miniature boxwood altarpieces and prayer beads had access to popular prints and contemporary works of art on which to base their designs. Whatever the inspiration, the drawings for the miniature objects were by necessity reduced in scale, and often segmented into discrete scenes to represent foreground, middle ground, and background. [20]

While sources, types of tools, and woodworking processes were largely identical in the fabrication of the large altarpieces and miniature boxwood objects, there was one significant difference in their design. Painters and gilders provided a preponderance of surface detailing on both the sculptures and architectural elements of the large altarpieces, but the nearly complete absence of polychromy on the boxwood carvings presented their carvers with the supplemental challenge of imparting sufficient detail to enliven the narrative for the viewer. Moreover, there were no gesso layers or paint to mask any inadequately carved passages.

The ideal medium for such intricate carving is boxwood, Buxus sempervirens, a fine-grained, dense hardwood that exhibits little variation in its working properties, both across and with the grain. The raw wood stock was imported into the Netherlands in pieces. During its initial preparation, the wood was cut to the required width, length, and depth, which demanded appropriately sized rip and crosscut saws. Cutting in mortise and tenon joints—which connect many of the multiple pieces comprising the triptychs and interior reliefs in the prayer beads—was the next step, requiring even finer saw blades. The surfaces intended to be seen were finished with planes and scrapers to remove the marks left by the saws.

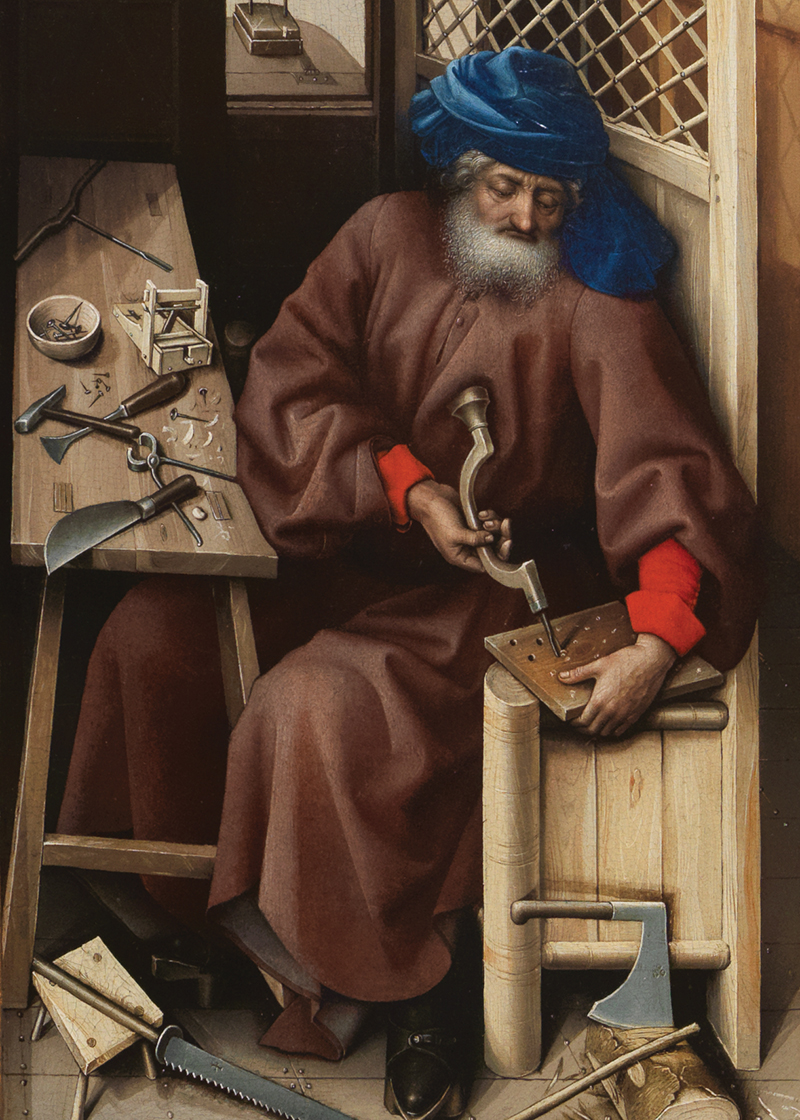

With these initial building blocks in hand, the artist transferred the design to its corresponding piece of boxwood by pouncing, tracing, or sketching. The multiple layers were then carved and joined together, much like a stage set. Specialized tools used by the carver were identical in shape and function to the saws, braces, augers, gimlets, files, flat chisels, U-shaped gouges and V-shaped gravers found in any contemporaneous woodcarver’s studio, excepting only their size. [21] Although none survive from this period, the set of tools belonging to renowned seventeenth-century Italian miniature carver Ottaviano Jannella give some idea of their scale and form.

Microscopic examination of complex, under-cut areas not visible to the viewer often retain the marks of fine drills called gimlets; these have diameters ranging from 0.3 to 1.0 mm, with a shell-like profile, a spiral taper, and a perimeter cutting edge. The carver also used these drills to add details such as the shape of a horse’s hock, or the openwork pattern of a king’s crown. On hand as well were a variety of knives with skewed blades with straight and curved cutting profiles, as well as hooked tools with assorted cutting edges that could reach around tightly compressed forms.

Exposed surfaces also retain evidence of their tooling, with cuts from V-shaped gravers and U-shaped gouges apparent in details of clothing, the spiral form of a soldier’s helmet, or a horse’s trappings, and with the stippled patterns of punches apparent across reserved areas. Less easily segregated are the successive cuts made by knives to model complex forms such as a horse’s neck or rump, or a figure’s physiognomy.

Such extraordinary detail suggests the use of magnification. Reading glasses in Europe are thought to have originated in Venice at the end of the thirteenth century. By the beginning of the fourteenth century, guild regulations differentiate between reading and magnifying glasses. While we do not have any documentary evidence for the use of magnifying glasses by late medieval woodworkers or sculptors, we know that contemporaneous goldsmiths were aware of the ability of plano-convex quartz cabochons to magnify objects and that they had been exploiting this in their metalwork to magnify relics. [22] Intriguingly, a pair of magnifying glasses is associated with the Jannella assemblage, similar in style to those used by several of the figures depicted in the boxwood reliefs.

The tools and joinery used in the fabrication of the boxwood objects aligns with the practices utilized in the creation of the large-scale altarpieces. The artist(s) responsible for the miniature objects used techniques, with uncommon virtuosity, often employed in the creation of the larger works, including: an additive approach to the building up of reliefs, joining together multiple layers, setting in discrete panels, and adding more minimally sized flourishes. [23] The thirty-year timeframe suggested for the fabrication of the boxwood objects—perhaps the equivalent of the lifetime of a single artist—suggests that our carver(s) may have started off with a grounding in the more established tradition of the larger altarpieces, easily applying that oeuvre’s technical sensibility on an infinitely more delicate scale. While many of the boxwood objects are very finely worked, there are also some of lesser quality. These could be early efforts, the product of a lesser hand, or fabricated for the market to appeal to the casual visitor or to elicit a commissioned work.

This Essay excerpted from Small Wonders: Gothic Boxwood Miniatures

Notes

[15] The authors’ findings are also presented in Scholten 2016, 514–577.

[16] Serck-Dewaide 1998 (83–89) and Jacobs 1998 (209–237) discuss the increasing complexity of large-scale altarpieces at the end of the fifteenth century, with sculptors integrating numerous individual figures carved from multiple pieces of wood composed to disguise their assembly.

[17] Inspired by the synchrotron- based computer X-ray tomography carried out on a Rijksmuseum prayer bead (Reischig et al. 2009), micro CT scanning was used to investigate multiple objects: the Thomson Collection’s boxwoods in the AGO were imaged by Andrew Nelson at the Sustainable Archaeology, Western University, Ontario, Canada (see Ellis et al. 2016) and six of The Met’s boxwood objects were scanned at Chesapeake Testing in Belcamp, Maryland (Chris Peitsch).

[18] KMS 5552, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen.

[19] Leewenberg 1968 and Scholten 2017, 24–51.

[20] Jacobs 1998, 222; Scholten 2011, 449.

[21] For a full discussion of the woodworking tools available to late medieval cabinetmakers and carvers see Goodman 1964. The space between the tines of medieval combs, which were often made of boxwood, can serve as an indicator of the fineness of medieval saw blades. The fretsaw is thought to have been invented in the middle of the sixteenth century (p. 153).

[22] Scholten and Falkenburg 1999, 25.

[23] Serck-Dewaide 1998, 83–84.