Like the prayer beads, the sculpted interior reliefs of the miniature altarpieces were generally built up and carved from multiple pieces. Overlaid onto one another, their outer dimensions were cut back to allow the ensemble’s placement within its architectural surrounds. The relatively thin panels provided the required access for the carving of all the interior elements, allowing the sculptor to model the figures free-standing or in high relief. This mirrors fabrication techniques used for large-scale altarpieces in the latter half of the fifteenth century whereby the narrative scenes became more complex, necessitating individual figures be carved from single blocks of wood and then assembled. [27]

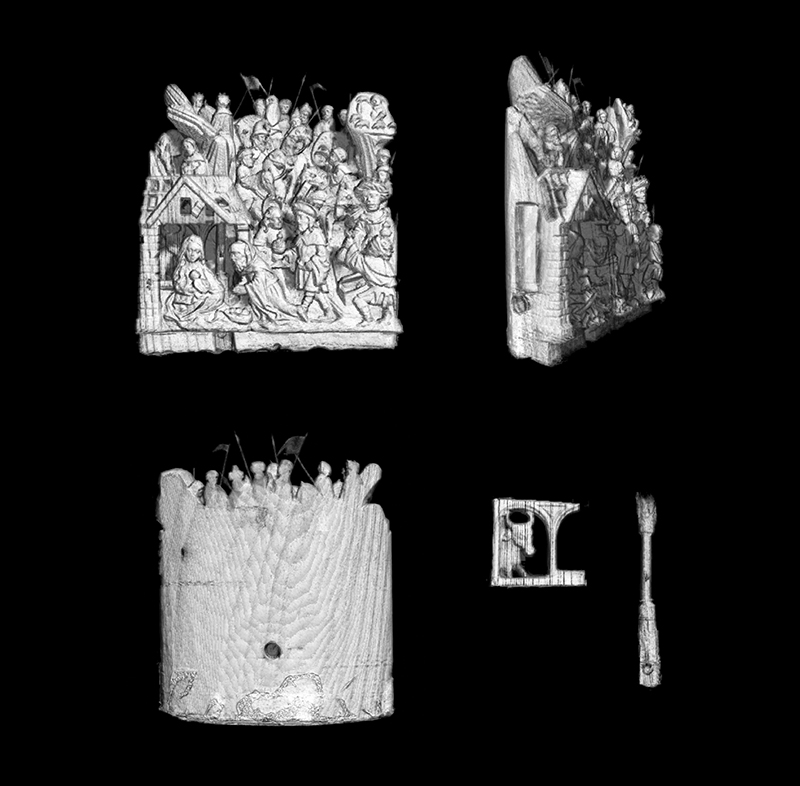

A miniature altarpiece in the Thomson Collection (AGO 34208) with a central corpus and hinged wings contains the most straightforward of all the triptychs’ central reliefs. The scene of the Adoration of the Magi is carved in the main from a single piece of boxwood.However, desiring greater verisimilitude and narrative depth than was possible within such constrained proportions, the triptychs’ sculptor(s) often added fully detailed elements that were either part of the original design or were conceived of during carving. In this instance, a separately carved relief with details of the stable and the head of the ox was slid into a mortise behind the Virgin in what would otherwise be an inaccessible area, and the column between the Virgin and the kneeling wise man inserted through the bottom of the larger relief. [28] Incredibly slender flags and spears have been inserted into drilled holes in the hands of the horsemen at the top of the composition: the extraordinary state of preservation of these fragile elements was undoubtedly enhanced both by their position at the back of the niche and the value and care accorded to these objects historically.

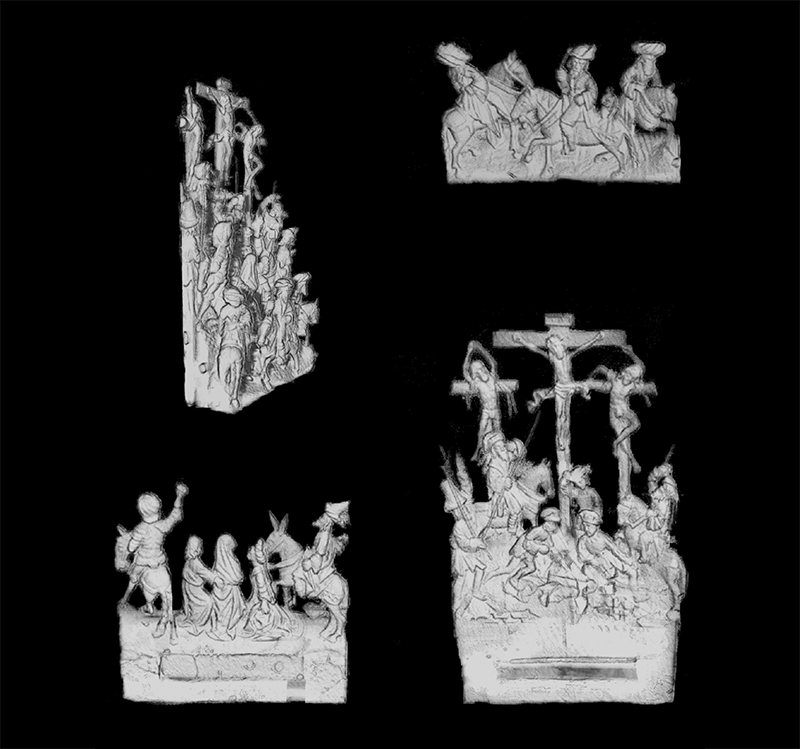

The central Crucifixion relief in The Met’s triptych (MMA 17.190.453) implements the multi-slab approach, overlaying three plaques of wood of varying heights to create its narrative. The first portrays the three horsemen in the foreground; the second presents the kneeling figures of the Virgin Mary and her attendants bracketed by another two horsemen; and the last shows the figures of Jesus and the thieves on their crosses, the triangular grouping of figures at the base of the central cross, two further horseman, and a standing figure holding a fork on the right side in the background. The composition was populated further with two standing figures behind and to either side of the central cross. Each is a distinct carving partially set into a carved-out recess within the cityscape carved into the back of the niche, which is part of the case housing the relief. The outstretched hand of the figure on the right was separately modelled and inserted into his sleeve.

An interior system of blind interlocking mortise and tenon joins were cut into the bases of the slabs to allow the different plaques to be disassembled and assembled consistently in register to one another, giving the carver the ability to constantly evaluate the composition and assure its sculptural continuity.

Given the size of the discs and plaques comprising the reliefs, it would have been difficult to hold them securely during shaping and cutting. Micro CT scans and visual examination reveal holes in the thickest part of each side of the plaques comprising the reliefs in the AGO and The Met’s triptychs as well as on the sides of the discs in the beads’ reliefs. [29] They serve no current function, but could have helped secure the wooden panels within a larger frame or against a support. The process was not unlike that used by artists working on large-scale wooden sculptures, who would mount a block of wood for their figure on a bench between two posts on a rotating vice, allowing the wood to be turned easily through 360 degrees. [30] Whether the boxwood pieces were intended to be rotated is unclear, but regardless, each plank of wood could be more securely braced and manipulated, allowing the sculptor to work with greater assurity.

Once complete, the individual carvings would be pinned and glued together and the reliefs set into their niches and secured in position. A more robust pinning system was implemented for the triptychs than that utilized for the prayer beads. A pin, now lost, was originally set in through the back of The Met triptych’s case and into the relief to secure it in place. Its absence suggests that the relief was removed from its setting at some point in its history, perhaps necessitating the current pins set through the front edges of the relief.

Notes

[27] Serck-Dewaide 1998, 83.

[28] The stables in the Adoration scene in triptychs at the State Hermitage (Φ 1641), and in the nativity scene in the Musée de Cluny triptych (13.532) appear to have a similar insert.

[29] The holes all have a rounded profile at their base characteristic of a spoon bit. A prayer bead (GG-VII 32 hh) from the Grünes Gewölbe, 27 Serck-Dewaide 1998, 83.

[28] The stables in the Adoration scene in triptychs at the State Hermitage (Φ 1641), and in the nativity scene in the Musée de Cluny triptych (13.532) appear to have a similar insert.

[29] The holes all have a rounded profile at their base characteristic of a spoon bit. A prayer bead (GG-VII 32 hh) from the Grünes Gewölbe, Residenzschloss, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden has similar holes.

[30] A good visual representation can be found in Georg Pencz’s engraving The Life of the Children of Mercury from his Planet series (1533).