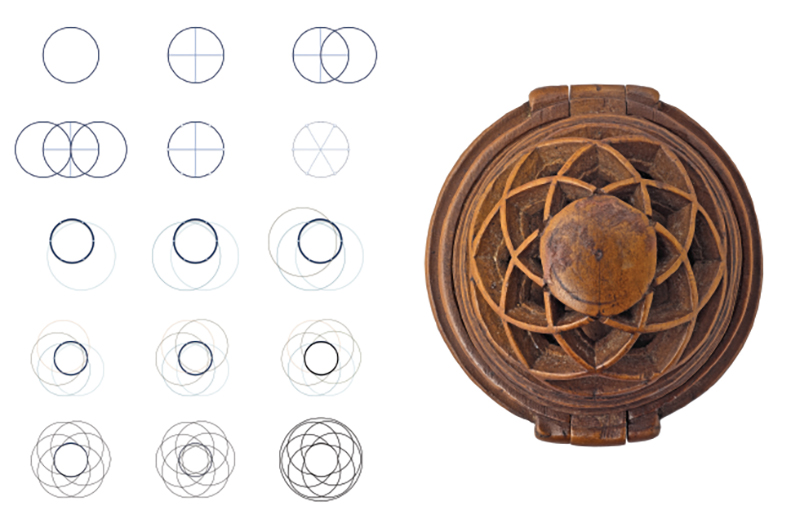

A comparison of extant prayer bead shells reveals two fundamentally different styles of tracery, and a third style that combines elements of both. All rely on the division of the prayer beads’ spherical domes into six or eight pie-shaped segments, with possible further division into twelve or sixteen parts. Only two tools were used in this enterprise: the compass and straight-edge. Division into six parts was accomplished by drawing three circles at the top of the spherical dome. One circle was placed at the centre and defined an area that would be left solid. Two other circles were centered at antipodes, or opposite poles, on the first circle’s circumference. The three circles shared the same radius. A hexagon was created when a straightedge was used to connect the four intersections of the circles in addition to the outer circles’ centres. Radii traveling from the centre of the first circle’s centre to these six nodes divided it into six segments. Division of the disc into eight parts was simpler: a straightedge was used to bisect the original circle, while another line bisected the first line at an angle of 90 degrees. Two additional lines, positioned at 45 degrees, were then drawn to divide the circle into eight equal segments.

The first style of tracery begins with the super-imposition of intersecting circles around the reserved circle of wood at the tops of the spherical domes. These additional circles rhythmically link nodes on the central circle’s circumference where it is intersected by the six or eight radii at the edges of the segments.

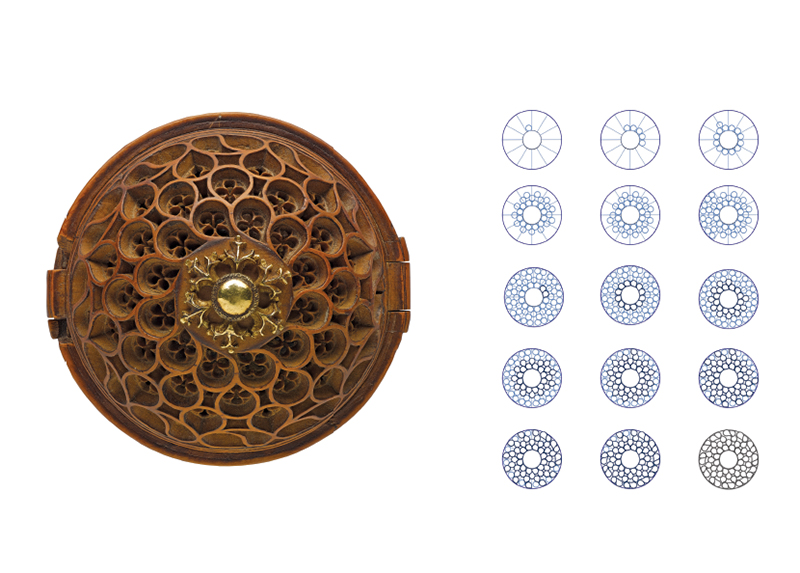

The second style was also executed largely with a compass but differs radically from the first style. Here, a considerable number of small circles punctuate the surface of the spherical dome. Once the dome has been divided into segments, these small circles are laid out within the radii, or by using the radii as their centres. The circles are sometimes retained but more often are transformed into teardrop shapes by opening up a quarter of their circumference. The teardrop shapes are sometimes elongated by placement of their originating circles farther from the desired end position of their tails.

The third style of tracery is the most complex. It uses partial circumferences, or arcs, of circles to link the first style’s looping and intersecting circles with the second style’s repeating patterns of small circles. The overall effect is that of a teeming, energetic surface, quite different from that expressed by the more staid second style of tracery.

It appears that the tracery designs of the prayer beads were most often rendered by starting at the top of the hemispherical domes. The designs tend to be well-ordered and logically composed around the central reserved circles at the top of the dome. As the tracery progresses toward the bottom of the dome, it can become slightly muddled, with circles not fitting as well and some repeating motifs truncated. In a few cases, however, it appears that the designs originate from the base of the spherical dome and proceed upward and inward. [26]

After the tracery designs were incised onto the hemispherical domes’ surfaces, the wood in the negative spaces of the pattern was removed with braces or pump and bow drills. For complex areas where control and visual access were of utmost importance, smaller gimlets substituted for larger drills. The initial clearing of the design would be to the depth of the mullions, with chisels clarifying their form and edges. The openings were then drilled through the remaining wall of the shell. In some cases, the openings echo the design of the dominant tracery, where others sport repeating patterns of trefoils, quatrefoils, and rosettes. The openings are further refined by adding triangular notches between the openings and then working from the interior to reduce the depth of the shell’s wall with gouges and files, and chamfering the inner edges of the opening.

This Essay excerpted from Small Wonders: Gothic Boxwood Miniatures

Notes

[26] An example is in the Wallace Collection, S281 (III G 427).