Prayer beads were intended to be carried, perhaps in some cases suspended from a belt, and to be handled. Some retain what appear to be the original metal fittings at their apex, used to attach them to a cord or to link them to other objects, while others retain telltale grooves at their tops and bottoms indicating the absence of now-lost hardware. Carved housings served to frame the action within and as a means of protection for the prayer beads’ delicate interior carvings. The shape of the exteriors is best described as two hemispheres connected by a thick girdle. The relief carvings sit inside the hollowed-out hemispheres. The girdle contains the hinge and clasp elements needed to open and fasten the object with a removable pin, now often lost, as well as in some cases inscriptions and decorative elements such as interlaced vines.

Although a number of the prayer beads have been altered over time, it appears that they were all originally designed to be opened by lifting the top half upward to reveal the interior carvings. The simple design of the clasp with a single male and female element supports this idea: it is considerably easier to open the prayer beads by pushing the male portion of the clasp upward while holding the female element stationary. Additionally, the upper half of the exterior shell is always slightly smaller than the lower one, allowing it to fit into the larger circumference of the latter when the bead is closed.

The sculptural program of eleven extant prayer beads was augmented with the use of wings and sometimes discs carved in low relief. The wings and disc remain attached to a prayer bead in the Thomson Collection that depicts the life of David from the Old Testament. Openings have been cut into the upper shell to receive the male portion of the two wings that pivot on hinge pins. Small hook-shaped elements partially recessed in the male portion of the hinge and clasp at the top and bottom of the upper shell swivel to hold the wings closed. Attached to the lower exterior clasp of the prayer bead’s shell with a comparatively complex hinging mechanism, is an extremely thin, delicate carved disc.

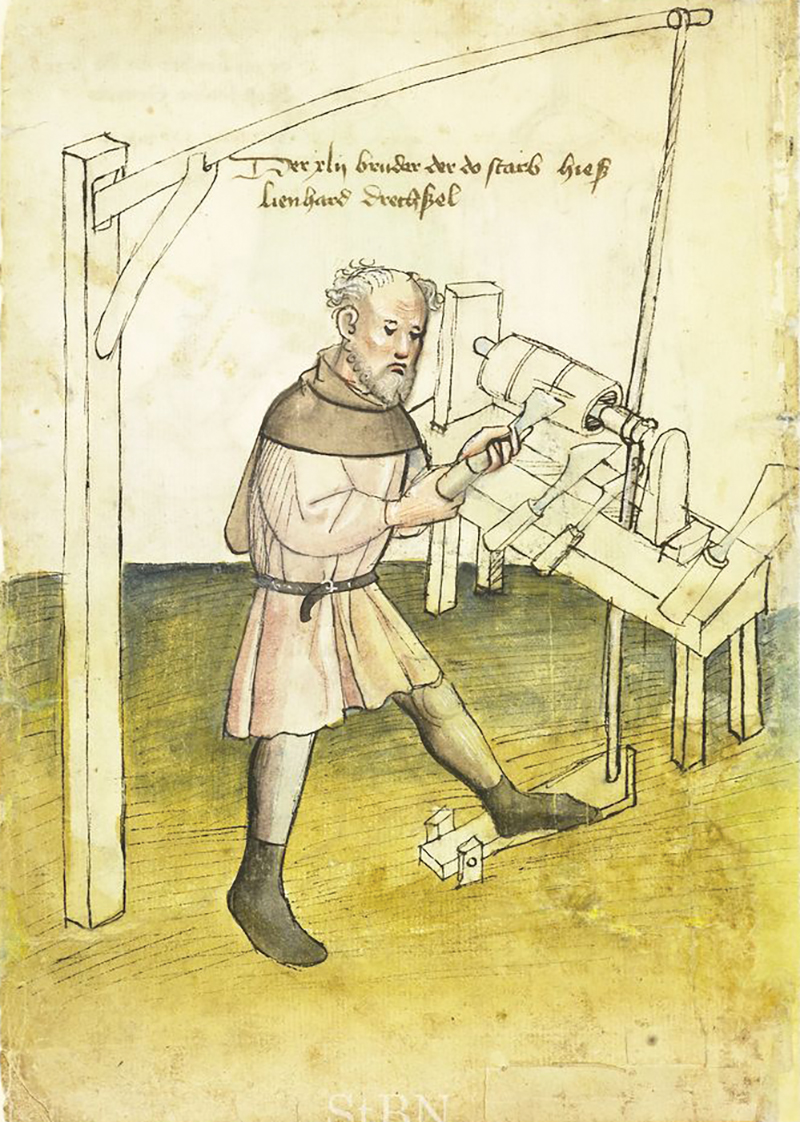

The pole lathe was commonly used in the medieval period to shape wood and metal. Diagnostic tool marks suggest that it was this tool that was largely used in making the prayer beads’ exterior shells. The lathe was powered by a foot treadle attached to a length of rope wrapped around one end of the horizontal shaft at the headstock. The lower end of the rope was pulled downward by pressing on a foot treadle and its opposite end pulled upward by a sapling of sufficient strength and spring. The back and forth motion of the rope caused the shaft within the headstock to spin. Because the worker used a foot to pump the treadle, both hands could be used for working the boxwood.

The first step in making the prayer beads’ shells was to secure and centre a rectangular piece of wood between the pin attached to the rotating spindle in the headstock and a stationary pin in the tailstock at the opposite end. Gouges, skewed chisels, parting tools and scrapers similar to those illustrated by Mendel [24] would be used to cut back the wood stock to a columnar form with a diameter equal to the largest required dimension of the prayer bead shell and of sufficient length to accommodate both of its hemispherical shells.

After this, a parting tool was used to cut the column into two discs, one for each half of the shell. Each of the resulting discs was then mounted against a faceplate attached to the rotating shaft, its interior hollowed out with chisels and gouges, and its lip given a stepped profile that would allow the two shells to fit together tightly once assembled.

Next, the disc was turned around and its stepped end placed against the faceplate and secured in this instance by the pin in the tailstock. Excess material was removed from the exterior to create the shell’s profile: a dome shape at one end and decorative, grooved rings cut in at the other. Sufficient material was retained to accommodate the male and female hinge elements, entwined vine tendrils, and other decorative elements.

At this point, the carvings were freed from the lathe and finished on the workbench. Decorative tracery designs were drilled through their walls and then further refined with hand tools. The introduction of the openwork patterns placed significant pressure on the shell walls, but the carver offset this problem by not cutting in the final intended depth of the walls until the very end when further material was removed from the shells’ interiors; marks of gouges, chisels and files used in this final step are still visible in some instances.

The prayer beads’ exterior shells have been decorated with perforated, geometric patterns: some boldly geometric and others partially organic in design. These are reminiscent of the openwork tracery often found on the predellas used to support large altarpieces and in the glazing and screens of gothic architecture in the churches and cathedrals that the makers undoubtedly knew and visited.

Those who now study prayer beads can attest to the impact, perhaps intended, of the artists’ use of tracery. Picking up, cradling, and opening a prayer bead depicting the Carthusian cleric François Du Puy (died 1521), with its extremely rare solid exterior shell (see p. 37), is a very different experience from handling a prayer bead with a shell that has been carved with an openwork tracery design.25 The most obvious and surely deliberate effect of the tracery is that the furrowed profiles carved into the shells allow the prayer bead to sit more securely in the hand, reducing the risk of slippage. The removal of dense boxwood from the prayer bead shells also reduced their weight considerably. This meant that the prayer bead would not hang heavily from a belt, distorting the line of the dress of its user and could be handled with less effort. Furthermore, the objects’ surprising lightness was perhaps meant to alert their users of their delicacy and the need to treat them cautiously.

This Essay excerpted from Small Wonders: Gothic Boxwood Miniatures

Notes

[24] “The so-called House Books of Mendel (Die Hausbücher der Nürnberger Zwölfbrüderstiftungen) illustrates a wealth of tradespeople, their workshops and their tools in the fourteenth century. The manuscript is now found at the Stadtbibliothek Nürnberg, Amb. 317. 317.20.

[25] Both exterior shells of a prayer bead in the British Museum (WB.235) are also solid and decorated in low relief, as is one of the exterior shells in a prayer bead at the Victoria and Albert Museum (265–1874).