Into the boxtree

"Into the boxtree." [1] One afternoon in the 1980s, acclaimed landscape historian Mac Griswold spied a garden on Shelter Island, New York, framed by boxwood trees that were twelve feet tall and fifteen feet wide. A far cry from the tame, decorative plants that frame the typical North American suburban garden, these, she realized, were hedges that had graced the property for centuries.

In fact, boxwood had come to Shelter Island some 350 years earlier, in 1653. Legendarily said to have been brought by Grissell Brinley Sylvester from England, [2] it is equally likely to have been acquired for Sylvester Manor in the Netherlands by Grissell’s husband Nathaniel, an Anglo-Dutch merchant. Its planting in the gardens reflected his family’s standing in society and his international connections, [3] for boxwood was recognized as an important commodity among the merchant classes of Europe by 1500.

Nothing to any purpose

North Americans assume that wood is a generally abundant and inexpensive material. However, we should not consider the relatively large numbers of surviving gothic miniature boxwood carvings—135 by our count—as evidence that they were “a dime a dozen.” Unlike works in silver or gold, wood carvings cannot be converted to ready cash and are far more likely to stand the test of time.

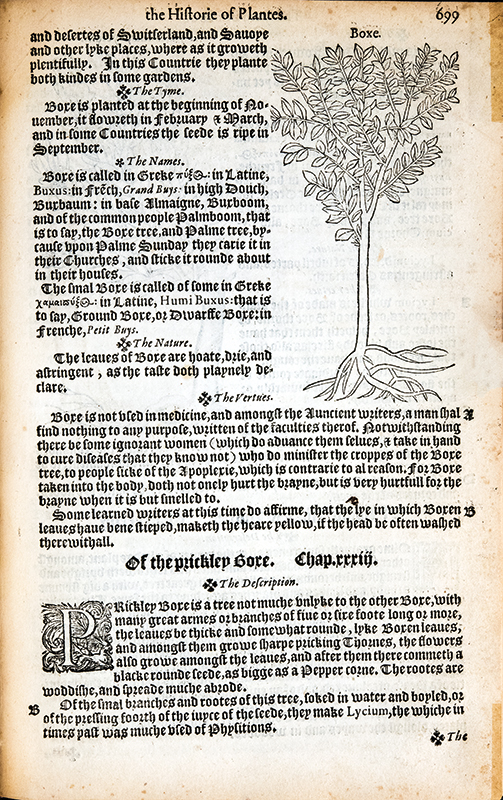

So why was boxwood valued? Early published herbals, important sources of information about the historical applications of plants, do not answer the question. They routinely say that Buxus sempervirens (boxwood’s Latin name) has virtually no medicinal application. The wood is mentioned as suitable for dyeing hair blond as early as the eleventh century (sometimes mixed with cabbage!), [4] but this use is hardly a matter of consequence. The physician and botanist Rembert Dodoens, in his widely-read Historie of Plantes, first published in English in 1578, summarily dismisses boxwood in his paragraph on its “Vertues,” saying “Box is not used in medicine, and amongst the Auncient writers, a man shal find nothing to any purpose, written of the faculties thereof.”

Many beautiful works can be made of it

By contrast, boxwood’s perfect suitability to carving had been recognized since antiquity. In a medieval context, its utility in making spice boxes and writing tablets was mentioned in the mid-fourteenth century, and its appropriateness as a container for holy water in the late fifteenth century. [5]

It is sometimes said that European artists’ enthusiasm for boxwood increased after the interruption of trade in ivory from North Africa following the Ottoman conquests, but its emergence as a prized material for works of art in the late medieval period is far more than a question of supply and demand. The artists who created the tiny carvings under discussion here conceived something entirely new—“small wonders” the likes of which had never been seen or imagined before—using a material perfectly suited to it that required long and careful cultivation.

Notwithstanding this remarkable achievement, almost no documentary evidence about commerce in miniature boxwood carving has been uncovered. There is a provocative note about the emerging industry in an English text dated between 1509 and 1529—contemporary with the datable pieces—suggesting a veritable international trade dispute over boxwood prayer beads. It refers specifically to prayer beads made of boxwood that have been hollowed out “like muske balles” that were being fabricated in Kent. These, complains the author, were being imitated by artisans in Flanders, thus undermining a burgeoning English industry. [6]

To beautify the place of my sanctuary

Beyond its suitability for carving, boxwood’s status was enhanced by the belief that it was mentioned in Christian scripture. In the Latin Bible of the medieval period, boxwood is one of three trees that the prophet Isaiah says will one day glorify the Temple of the New Jerusalem: “The glory of Lebanon shall come to thee, the fir tree, and the box tree, and the pine tree together, to beautify the place of my sanctuary: and I will glorify the place of my feet.” [7]

With the authority of the prophet Isaiah at its root, boxwood became entwined with Christian story and practice over the course of the Middle Ages. For example, according to the instructions for the twelfth-century Palm Sunday procession at Chartres, the bishop blessed both palms and boxwood for distribution to the faithful. [8] Boxwood assumes pride of place alongside the palms that are mentioned specifically in Gospel accounts. Churchmen commenting on such ceremonies, in which laurel might also be used, considered both palm and boxwood to be symbols of virtues that the faithful present to Jesus.

As an evergreen, boxwood had long been considered emblematic of eternal life. [9] In modern Polish tradition, sprigs of boxwood are used to decorate baskets known as Swieconka on Holy Saturday. [10] While it is not known when that tradition was first put into practice, it echoes the medieval tradition of linking boxwood with Palm Sunday.

Some medieval writers advanced the notion that boxwood was one of the woods used for the cross on which Jesus was crucified. How resonant, then, that prayer beads of carved boxwood, so often representing the Way to Calvary and the Crucifixion, were carved from the very material from which the cross itself was formed. Moreover, the inscriptions sometimes spell out the Good Friday prayers extolling the virtues of the “sweet wood” of the cross, [11] while the exteriors of boxwood prayer beads are sometimes ringed by a crown of thorns. Sight and touch join forces to facilitate meditation on the drama of the Christian story, to cradle a virtual walk on Jerusalem’s Via Dolorosa in the palm of the hand.

Boxwood drives out the devil

At the dawn of the sixteenth century, boxwood and the recitation of the Lord’s Prayer, called the Pater Noster (Our Father) in the Catholic faith, were paired in popular notions of how to fight evil. In his Margarita Medicine, first published in 1497 as a kind of medical self-help book for the poor, [12] Johann Tollat of Vochenberg explored both herbal remedies and practical approaches to life’s challenges. Tollat claims that anyone wanting to be chaste should inscribe the Our Father prayer on a sheet of paper and carry it with him: “It takes away evil desire and makes one chaste.” Should that prove ineffective, further steps could be taken: “Boxwood drives out the devil too, so that he can have no place in the house, and therefore Platearius says one should bless [the house] on Palm Sunday.” [13] Tollat thus links contemporary perceptions and practices surrounding boxwood to beliefs expressed by physician Matthaeus Platearius, some 350 years earlier, in the first half of the twelfth century.

Guardians of history

Conventional wisdom surrounding boxwood has endured like the tree itself. For Mac Griswold, the 350-year-old standing boxwoods that she found at New York’s Shelter Island are “guardians of history.” [14] No less than those, miniature boxwood carvings from the sixteenth century stand in quiet witness to history and to an almost magical transformation of nature into art.

This Essay excerpted from Small Wonders: Gothic Boxwood Miniatures

Notes

[1] W. Shakespeare, Twelfth Night, act 2, scene 5.

[2] See the Sylvester Manor website.

[3] M. Griswold, The Manor: Three Centuries at a Slave Plantation on Long Island (New York: MacMillan, 2013), 98.

[4] In The Trotula, attributed to a woman of that name in Salerno. See The Trotula: An English Translation of the Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine, M.H. Green, ed. and trans. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001); V. Sherrow, Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History (Westport CT and London: Greenwood, 2006), 267.

[5] Both cited in V. Gay, Glossaire archaologique du moyen age et de la renaissance 1 (Paris: Société bibliographique, 1887), 235.

[6] G.C. Williamson, Catalogue of the Collection of Jewels and Precious Works of Art, The Property of J. Pierpont Morgan (London: privately printed at the Chiswick Press, 1910), 58–59; cited in Romanelli 1992, 21.

[7] Isaiah 60:13.

[8] C. Wright, “The Palm Sunday Procession in Medieval Chartres,” in The Divine Office in the Latin Middle Ages: Methodology and Source Studies, Regional Developments, Hagiography. Written in Honor of Professor Ruth Steiner, M.E. Fassler and R.A. Baltzer, eds. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 347.

[9] S.J. Record and G.A. Garratt, “Boxwoods,” Yale University School of Forestry Bulletin, no. 14 (1925), 7.

[10] S. Hodorowicz Knab, Polish Customs, Traditions and Folklore (New York: Hippocrene Books, 1996), 102.

[11] The “Adoratio Crucis,” or Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross. See Romanelli 1992, 145–151.

[12] See H. Walther, “Johann Tallat von Vochenberg: Zu seiner Biographie und seinem Arzneibuch (1497),” Sudhoffs Archiv 54 no. 3 (1970), 293.

[13] The full title of Tollat’s work is Arznei Buchlein der Kreutter, oder Margarita medicine. It was published in Augsburg in 1502, following an earlier edition published in Memmingen in 1497. There were eleven editions between 1507 and 1532. Cited in H.C.E. Midelfort, A History of Madness in Sixteenth-century Germany (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999), 142.

[14] Griswold 2013, 4.